Charlestonians have long been known for enjoying a tipple (or two or three), and today’s exploding culinary scene and artisanal entrepreneurial efforts mean there’s a greater variety of spirits, mixers, and libations than ever. And while the alphabet’s 26 letters kept us from including everything we love, when it comes to Charleston cocktails, there’s something for everyone, from A to Z.

Written by Kinsey Gidick

- A TO Z

- VIDEOS

- PRINT FEATURE

At FIG, bartender Andrew King stocks 15 bottles of amaro, but if he had his druthers, he’d double that. “It’s definitely an ingredient that swept me away,” he says.

Amaro (or plural: amari) is an herbal liqueur, traditionally Italian; though France, Germany, Poland, and the US have joined the digestivo game, according to Saveur. Amari’s history traces to medieval monks who made herbal tinctures as healing agents. Ask King, and he’ll likely agree there’s still some palliative power to the liqueur that’s often enjoyed neat or with a twist of citrus.

And while the bitter spirit took some tenacity to introduce here, “guests are coming back and asking for new ways to try it,” he says. After assessing a person’s reaction to the bold and medicinal Fernet-Branca—“some spit it out, so I gauge the wince”—King offers lighter-bodied styles like the lightly sweet and floral Montenegro. For the uninitiated, King suggests asking your bartender to cut it with some soda—a great entry level to this bittersweet liqueur.

Bloodshot Moon (Serves 1)

- 1½ oz. Fernet-Branca

- 1 oz. Old Overholt straight rye whiskey

- 1/2 oz. Luxardo Maraschino liqueur

- 2 dashes lemon bitters

- 1 lemon peel

- 1 orange peel

Place all liquids in a shaker filled with ice. Shake well, pour into a rocks glass, and garnish with lemon and orange peels.

Before The Darling’s The Captain Bloody Mary hits the table, it’s gone through four stations, getting accessorized with a hush puppy, a king crab claw, a lobster claw, and two pickled shrimp. A seafood tower—minus the, well, tower—it’s a conversation starter, to say the least. “It’s been a huge success,” says bar manager Dan Williams, who agrees that The Captain’s audacity speaks to the seriousness with which Charlestonians approach their Bloody Marys. It’s just not brunch without a bevy of bloodies. Local iterations vary, from a country ham-garnished version at Husk to a golden yellow tomato drink topped with grilled baby corn at Millers All Day. In fact, Charleston loves Bloody Marys so much, the city has spawned at least four local Bloody Mary mix purveyors (see above). That said, Zing Zang fans can still get their favorite mix, and a great brunch, at places like Marina Variety Store.

Charleston is not apple country, but that hasn’t stopped cider maker Ship’s Wheel from placing some roots here. Last spring, the company began quenching the city’s thirst for a beer alternative, and now its owners, the Jamison family, are poised to bring the first hard cider tasting room to the Lowcountry. “We really thought that cider as a category was not fully represented,” says patriarch Scott Jamison of the nascent company.

Scott and wife Cindy grew up in coastal New Jersey but spent the majority of their adult lives in Virginia, where their love of cider grew. When their kids moved to Charleston, they packed up too, but Scott says they couldn’t find the cider flavors of home here. Today, Ship’s Wheel produces three varieties (Original Blend, Dry Hopped, and Summer Splash) sourced from orchards in New York as well as the Old Dominion, and beginning this spring, you can sample from the makers when their tasting room opens in Park Circle.

Caption:

Find Ship’s Wheel Hard Cider at Lowlife Bar on Folly Beach and The Gin Joint downtown, as well as both Whole Foods locations.

Credit: Photograph by Sarah Alsati

When you consider Charleston’s history of pirates and privateers drinking and gambling down our cobblestone streets, it’s no wonder this city appreciates a crusty, dusty dive. Just as Blackbeard’s men might have shared a dram of rum at The Seafarer’s Tavern (today a liquor store at 120 Broad Street), we’re drawn to the come-as-you-are, workaday welcome at places like Richard’s Bar & Grill in Mount Pleasant (RIP); Gene’s Haufbrau in West Ashley; and the peninsula’s Cutty’s, AC’s, and Moe’s. Don’t believe us? Consider that King Street’s Recovery Room holds the record as the No. 1 seller of Pabst Blue Ribbon cans in the world. That’s right, we said world.

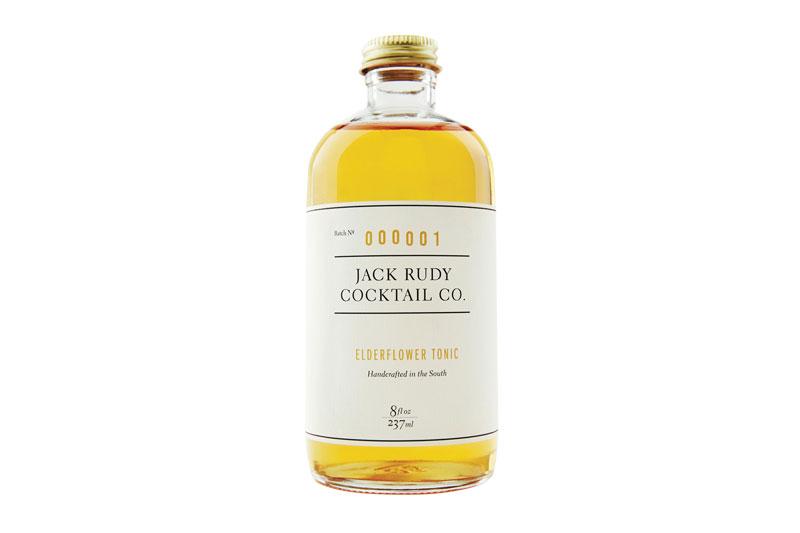

Brooks Reitz, founder of Jack Rudy Cocktail Co. (and co-owner of Leon’s Oyster Shop, Little Jack’s Tavern, and Melfi’s), was already established in the beverage industry when he had his elderflower epiphany. “I loved St. Germain,” he says of the French elderflower liqueur. “When it came out, it was the bartender’s ketchup. It made everything taste delicious. There’s not a spirit that it wouldn’t mix with.”

Flash forward to a Thanksgiving visit to his native Kentucky five years ago, when his dad pulled out a bottle of elderberry wine, made from berries that grow wild along the railroad tracks in his hometown. “That struck me,” says Reitz. “I thought you could only get it in the French Alps, not Kentucky.” So he began playing with dried elderflowers and realized that their “grapefruit quality without acidity” and rich mouthfeel would be a perfect mix in a bourbon, tequila, or rum drink. Thus his Jack Rudy Elderflower Tonic was born. You can order a 17-ounce bottle from jackrudycocktailco.com for $16 or visit Leon’s to try the Elderflower G&T.

Recipe:

Elderflower G&T

(serves 1)

- 2 oz. gin

- 3/4 oz. Jack Rudy Elderflower Tonic

- 4-5 oz. soda water

Combine the gin and tonic in a collins glass with ice. Top with soda water, stir, and serve.

Credit: Photograph courtesy of Jack Rudy Cocktail Co.

In the summer, King Street’s Uptown Social sells roughly 500 frosés a week. “That’s definitely our most popular frozen drink,” says bartender Matt Watson. The trendy wine slushy hit the F&B scene hard when it arrived in 2016. And thanks to bachelorette parties and a summer that essentially lasts six months, frosé isn’t going away anytime soon. Many places sell the icy rosé, but Uptown Social mixes theirs with High Noon Grapefruit vodka to give it an extra little kick.

Credit: Photograph by Sarah Alsati

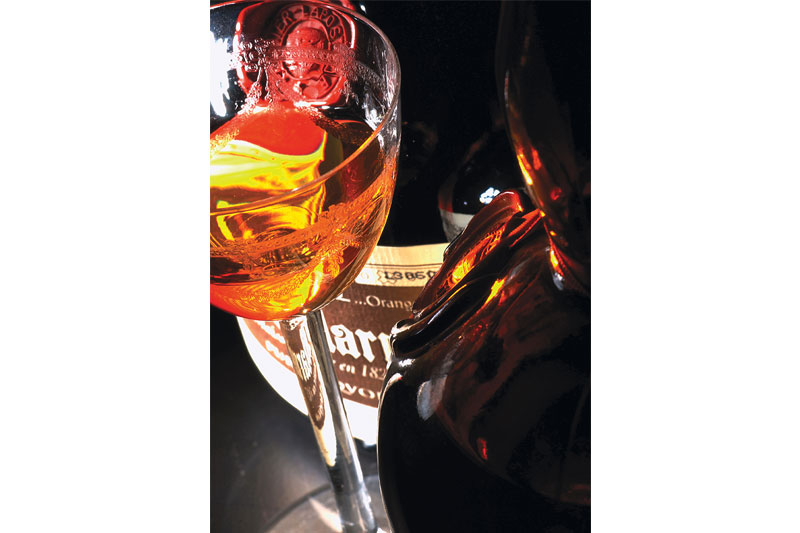

When it comes to local bartender lore, few stories can top the “Great Grand Marnier Visit.” First, you need to know that the orange-flavored, Cognac-based French liqueur that’s predominately used for cooking became the shot among the local F&B crowd roughly 20 years ago.

According to FIG bartender Andrew King, the bigwigs at Grand Marnier, curious to find out why their liqueur was now the Charleston “bartenders’ handshake,” flew in a team to meet the top sellers of “GrandMa,” as locals affectionately call it.

“The way I understand it is that Grand Marnier wanted to celebrate the city for being the highest seller stateside, so they invited a bunch of bartenders to Henry’s on Market Street and brought in an anniversary edition of 100-plus-year-old Grand Marnier,” says King. “The locals started turning up the bottles and shooting it, and the Grand Marnier representatives got so disgusted, they left the party and never came back.” Or so the story goes…. Oh, mon Dieu!

No local distillery has gained more acclaim than High Wire, and for good reason. In addition to their beloved Hat Trick Gin and the 2014 Bronze Medal ACSA Spirits Competition-winning Sorghum Whiskey, they’ve made some unusual moves in the micro-distilling world that have yielded incredible results.

In 2013, Scott Blackwell and Ann Marshall’s King Street operation brought rum-making back to the peninsula. A year later, the couple produced bourbon from Jimmy Red Corn, a nearly extinct breed, and in 2015, they introduced their Bradford watermelon brandy, made from a little-known heirloom fruit that the Bradford family had been growing in nearby Sumter for 100 years. Last summer, High Wire distilled 10,000 peaches from Titan Farms in Ridge Spring that are currently aging in refurbished French oak barrels. Considered by some spirit historians to be the “first truly American spirit,” peach brandy will finally return to South Carolina this July.

“Scott and Ann are among the few distillers to understand that spirits are an agricultural product,” says Imbibe contributing editor Wayne Curtis. “They start with the field in their planning rather than the distillery, and the result is unique flavor.”

Caption: Scott Blackwell and Ann Marshall at High Wire

Credit: Photographs by Sarah Alsati

Clear, boulder-size ice cubes are still a thing for a reason. Bartenders love those eye-catching cubes because of their scientific properties, says Miguel Buencamino, a local libations expert and the face behind wildly popular Instagram brand Holy City Handcraft.

“The cloudiness in your refrigerator ice is caused by trapped air bubbles,” he explains. “The outer layer of clear ice tends to melt a lot faster and dilutes your drink faster.” A cube that’s completely clear provides a more consistent flavor experience. That’s why places like The Gin Joint freeze and cut their own ice using a Clinebell machine and The Dewberry special orders its cold stuff from Ice Age Ice Sculptures in North Charleston.

Kentucky may act like it owns the mint julep, but according to historian Robert Moss, author of Southern Spirits: Four Hundred Years of Drinking in the American South, the Bluegrass State’s claim is the result of a wildly successful marketing campaign by the Kentucky Derby, and not the true origin story. Moss asserts that Virginia was the likely birthplace for the cocktail in the early part of the 19th century, and Charleston can take credit for bringing it en vogue. “If you went to the Mills House Hotel in the 1850s, juleps would have been one of the most popular drinks,” he says.

The julep was initially concocted as an “antifogmatic,”or morning eye-opener. “You have to remember, Southerners drank all day long in the 1830s or 1840s,” continues Moss. “The term ‘julep’ meant a compound you’d use to make medicine—a little sugar mixed with your spirit, rum or brandy in the early days. At some point people started putting mint into it.”

Today, bourbon has become the julep spirit of choice, and you can enjoy a fine example of the classic at The Dewberry. However, Moss also recommends trying one with peach brandy—the way juleps were originally made in the 1830s. Lucky for Charleston, it just so happens that in July, High Wire Distilling Co. (opposite) will release its inaugural peach brandy, so you can experiment for yourself.

Caption: Find a classic version of the bourbon mint julep at The Dewberry’s The Living Room bar.

Credit: Photograph by Shell Royster

A “keg-batch” is a large quantity of pre-mixed drinks. “The main reason bars make them, honestly, is for ease,” says Edmund’s Oast beverage director Jayce McConnell. In a high volume place, “it’s good to have a few pinch-hitter cocktails,” he notes, ones that are ready for the bartender to simply pour over ice and perhaps top with a sparkling wine. But efficiency doesn’t have to deduct from flavor. For the holidays, McConnell served a French 75-esque drink with cranberry, spice, and gin. Pop into Edmund’s to see what he’s got batched this season.

Photo credit: Photograph by Libby Williams

Charleston’s legal history with booze is about as complex as some of the world-class cocktails being crafted throughout the Holy City, according to attorney Brook Bristow of Bristow Beverage Law. “The state liquor laws are the reason you can’t purchase spirits from a box store on Sundays, why there were mini bottles for more than 30 years, and why the state didn’t have a production distillery until 2009,” he explains of the complicated mess of regulations brought on by South Carolina’s embrace of the temperance movement.

“Nationally, Prohibition took place from 1920 to 1933, but South Carolina voters were well ahead, having passed a ban in 1892,” Bristow adds. “Even after Prohibition, the sale of liquor didn’t return to the state until 1935.” That said, Bristow believes our spirits laws are fairly progressive today compared to neighboring states. “Up until recently, North Carolina didn’t allow restaurant alcohol sales on Sundays until noon,” he says. “In Charleston, there’d be a riot if you couldn’t have a mimosa with brunch.”

Colonial Charleston was instrumental in the creation of Madeira as a value-esteemed wine, says historian Robert Moss. It turns out the Portuguese wine actually improved during the long Atlantic passage. “When wealthy planters began specifying things, like the addition of a bucket of brandy, it only seemed to get better,” says Moss.

An outbreak of mildew wiped out Madeira in the late 1850s, he notes, and after the Civil War, planters had to sell their stores to New York industrialists to recoup their wartime losses. “Delmonico’s in New York would have on its wine list a Madeira from the Belvederes or other Charleston family names,” Moss adds.

Today, some of those bottles still exist, and when he’s really lucky, Charleston Grill wine director Rick Rubel can acquire them. “I always keep 10 bottles of Madeira on the menu,” Rubel says, but those rare finds, like the 1863 vintage he was able to regularly secure eight or so years ago, have begun to literally dry up.

“Then I could get one for about $500. Today they’re $1,000,” he says. But that doesn’t mean you can’t taste the past. Charleston Grill offers a surprisingly affordable Madeira flight. For $45, you can taste three styles—one as old as 1908 and another as recent as 1977.

Caption: The Madeira flight at Charleston Grill; taste three vintages for $45.

Credit: Photograph by Shell Royster

The national natural wines trend has landed in town. In fact, Food & Wine named Park Circle’s Stems & Skins one of the 15 most important natural wine bars in America, and Renzo, the posh little eatery that opened last year on Huger Street, has dedicated its entire wine list to natural producers. So what’s the deal with natural wine?

“Nothing’s taken away, nothing’s added,” explains Renzo co-owner Nayda Freire. “That means the wine-makers aren’t adding yeast or sugar or sulfur. They let the wine speak for itself as much as possible and let the terroir shine through.” Which is to say, historically speaking, there’s nothing new about “natural wines” at all.

For neophytes, Freire recommends Gamay, “as many producers in Beaujolais have long championed natural wine-making, and the grape lends itself to bright, easy-drinking, and food-friendly expressions,” she says. And for the natural wine enthusiast, Freire leans toward Jolie-Laide Trousseau Gris. “It’s a skin-contact white from a California producer known for amazing site selection and low-intervention practices,” she explains. “The grapes are farmed organically, foot-stomped, and the wine is aged in neutral barrels. Scott Schultz makes some of the more elegant, disciplined examples of this style.”

Caption: North Central neighborhood eatery Renzo features only natural wines on its list, including underrated varietals and boutique bottles from small, family-run, and terroir-driven wineries.

Ask the food-and-bev industry crowd where to get the best old-fashioned in town, and they’ll almost universally respond, “Proof.” Craig Nelson, the King Street bar’s owner, can take all the credit for making something, well, old, sought-after again. “It’s one of the basic cocktails, but it often gets overdone,” says Nelson. Instead of doctoring his with maple syrup or blood oranges or some other hip twist, Nelson keeps it simple: sugar, bitters, spirit, and water. “I use Jim Beam rye whiskey; it’s rough around the edges, but the sugar and the bitters smooth it out,” he explains. The formula may sound straightforward, but it’s a recipe for success. Proof serves 100 of them a week.

Proof Old-Fashioned

(Serves 1)

- 1 white sugar cube

- 1 drop water

- 3-4 dashes Angostura bitters

- 2 oz. Jim Beam rye whiskey

- 1 orange twist

- 1 brandied cherry

Place sugar cube in a rocks glass, add water and bitters, and muddle to dissolve. Add whiskey and ice cubes and stir. Garnish with the expressed orange peel and a brandied cherry.

Caption: “We serve a demi-glace spoon on the side so the guest can stir it,” says Nelson, noting that stirring helps dissolve the sugar and sweeten the sips.

Credit: Photograph by Sarah Alsati

Charleston and punch go together like Sunday service and blue blazers. And while we can’t lay claim to its invention—its first appearance in writing was by an Englishman, according to David Wondrich in his delicious deep-dive, Punch: The Delights (and Dangers) of the Flowing Bowl—local receipts for the communal libation abound, such as the classic St. Cecilia Punch, named after the exclusive musical society. To get a taste of the spiked party staple, visit Doar Bros. on Meeting Street for a $10 quaff of their Punch du Jour, a rotating seasonal mixture, or step into Cocktail Club for its true blue punch bowl serving four to six ($50). Our choice? Uncle Joe’s Juice Cleanse made with Firefly Classic vodka, fresh cucumber and lime juices, lemongrass, mint, and soda.

Caption: The Cocktail Club’s First President Punch combines rye whiskey, brandy, dry orange curaçao, lemon juice, orange bitters, simple syrup, soda water, and orange slices.

Credit: Photograph by Andrew Cebulka, courtesy of Cocktail Club

In 2016, seemingly overnight, Charleston became a barbecue destination, centered around downtown’s pulled-pork triangle—Rodney Scott’s, Home Team, and Lewis Barbecue. And where there’s smoky meat, there’s beer. Home Team features the most extensive selection of draft and bottled brews, including local suds such as Holy City’s Pluff Mud Porter. But to get into beer cocktail territory, you’ll have to visit Lewis and order the michelada. Texas native John Lewis’s “secret” riff on the Mexican beer and lime juice drink is a nod to his Southwestern roots and a refreshingly spicy complement to the ’cue.

Caption: Try Lewis’s spicy michelada or one of 11 draft brews with your ’cue.

Credit: Photographs by Libby Williams

“Walking the streets of Charleston in the late afternoons of August was like walking through gauze or inhaling damaged silk,” Pat Conroy wrote in The Lords of Discipline. And that’s been the case since the first English settlers landed in 1670. Naturally, Charlestonians have always been in search of thirst-quenching drinks. Enter rum.

“Rum was the beverage of choice for the first 150 years of the city,” says Robert Moss. At the time, brandy and strong liquors were expensive, but rum—made in the Caribbean with the by-product of sugar-making—was cheap and readily available. Which is to say, all you mojito and dark and stormy fans have the port to thank.

“Ships from England would sail down the coast of Europe, load up on Madeira, sail to the Caribbean and load up with rum, take the rum to Charleston and sell it, load up the holds with rice, and head back to England,” says Moss.

Today, we’re seeing a rum resurgence showcased in places like Cane Rhum Bar on East Bay and seafood palace The Ordinary. There you can choose from a dozen rum drinks. Moss encourages you to start with the bar’s classic daiquiri—one part fresh lime juice, one part simple syrup, and two parts light rum.

Caption: Take your pick among the array of daiquiris at The Ordinary.

Credit: Photograph courtesy of The Ordinary

According to the Charleston Chapter of the Surfrider Foundation, more than 660,000 plastic straws are used daily in the city’s bars and restaurants. Those discarded single-use sippers are a pollution nightmare, especially for a coastal community. That’s why Surfrider and the Charleston Chapter of the US Bartenders’ Guild teamed up for Strawless Summer, a campaign to raise awareness for this issue that harms sea life and litters beaches.

Last summer, 230 local restaurants took the pledge to nix straws. And though long-term change is slow, the impact can be seen in places like the Charleston Music Hall, which has shifted entirely to the paper variety. It might take a few more summers, but with the push to give up plastics—evidenced by the plastic bag bans in Mount Pleasant and Charleston—our coastal protection crusaders are hopeful straws could be next.

Captions: Find packs of fun paper straws ($3 for 25) at CannonboroughCollective.com.

Fleet Landing offers reusable metal straws for a nominal price with drink purchases.

Credit: Photographs by Sarah Alsati

Eighty-five years after Don the Beachcomber opened in LA, the cult of tiki continues, and Charleston is no exception. Although downtown’s South Seas Oasis shuttered at the start of the year, there’s long-standing kitschy haven Voodoo in Avondale. And now Folly is home to Wiki Wiki Sandbar, restaurateur Karalee Fallert’s 6,500-square-foot oasis of all things tiki, including more than a dozen potent island-inspired drinks.

So how do you think this faux Polynesian genre endures in a city that’s seemingly all about traditional sophistication?

A) Hot days

B) The city’s “rum”ance

C) An unquenchable thirst for something tall and strong

D) All of the above

If you selected D, treat yourself to a mai tai because the truth is, in Charleston, where citizens are always looking to have a good time, tiki just makes sense.

Caption: For $10, you can sip the Pineapple Incident, a Pineapple Dole Whip, Jamaican rum, and whip cream concoction. It’s one of 14 Polynesian cocktails at Folly Beach’s Wiki Wiki Sandbar.

Credit: Photographs by (Exterior) Kayla Beck & courtesy of (Drink) Wiki Wiki Sandbar

If you are one to indulge (or overindulge) in the city’s rich fare, you’ll want to know about this German digestif, a seemingly magical antidote delivered by the “shot” from tiny paper-wrapped bottles. “Underberg is 44 percent alcohol by volume,” says Brandon Plyler. “Knocking down the fairly salty, bitter drink after a big meal refreshes you and makes the bloated feeling go away.” Plyer’s such a fan, that he and Jayce McConnell named their new podcast, Pocket Liquor, about “all things quaffable,” after the mini bottles that have become popular among local F&Bers. The Ocean Room at The Sanctuary has long been clued into Underberg’s gastric magic, proffering guests a crystal dish filled with the bottles post-dinner. Not heading to Kiawah any time soon? You’ll find the petite amber-colored elixirs on most liquor store counters.

Captions: The Underberg family has been producing the herbal digestif in Rheinberg, Germany, since 1846.

Gregg Ervin delivers the Underberg service at The Ocean Room.

Credit: Courtesy of Kiawah Island Golf Resort

In the same way FIG’s Andrew King is evangelizing amaro, at Stems & Skins in Park Circle, Matt Tunstall preaches the beauty of vermouth. “We gave it away for the first three months,” says Tunstall, but he’s made many of his guests apostles of the aperitif.

“Vermouth is made from fairly natural wine, then aromatized by adding stems, seeds, and flowers and letting that set. Then, it’s fortified with a grape brandy for 17 to 19 percent alcohol,” he explains.

Tunstall’s love of the wine developed during his travels in Europe, where its enjoyed before a meal. “The traditional garnish is anchovy stuffed olives,” he says. “That salty brininess is great with a sweet vermouth.”

Currently Stems & Skins has nine bottles to choose from, but Tunstall is also making his own. “I bought a vermentino from Corsica that we’re playing with.” Ask him nicely, and he’ll be glad to let you try it.

Caption: Park Circle’s Stems & Skins offers many styles of vermouth, from the traditional Italian Contratto Vermouth Rosso to Dolin’s sweet, herb-centric Chambéry Blanc (left).

Credit: Photographs by Sarah Alsati

“American whiskey—bourbon, in particular—was pretty dead in the 1970s and ’80s,” says Robert Donovan, a founding member of the Charleston Brown Water Society (CBWS). “In the early ’90s, bourbon started seeing a sharp uptick in sales, especially in the US and Japan.” Suddenly products like Gentleman Jack; Wild Turkey Rare Breed; and Jim Beam’s premium lines, Booker’s and Baker’s, hit the market.

A few years later in Charleston, a perfect storm of longtime bourbon drinkers searching out small-batch and single-barrel releases, plus the hype surrounding limited-edition Pappy van Winkle, dovetailed with the opening of bourbon emporium Husk Bar.

“From this the Charleston Brown Water Society was born,” says Donovan. The organization, founded by a few Husk bartenders and one regular, set out to “increase the general public’s knowledge of whiskey and many other fine brown spirits.”

Today, local whiskey lovers can raise a glass to Husk and the CBWS’s whiskey evangelism, as they can make a brown-water crawl (provided they Uber), from Husk to the Thoroughbred Club, The Gin Joint to Halls Chophouse, Proof to Seanachai on John’s Island. And if that’s not enough, they can also get their own liquor lockers at King Street’s new Bourbon & Bubbles. As Donovan can attest, in Charleston, we’re preaching to a whiskey-loving choir.

Caption: Gerry Kieran stocks more than 100 whiskeys, including 57 from Ireland alone, at his Seanachai Whiskey and Cocktail Bar on John’s Island.

Credit: Photograph by Shell Royster

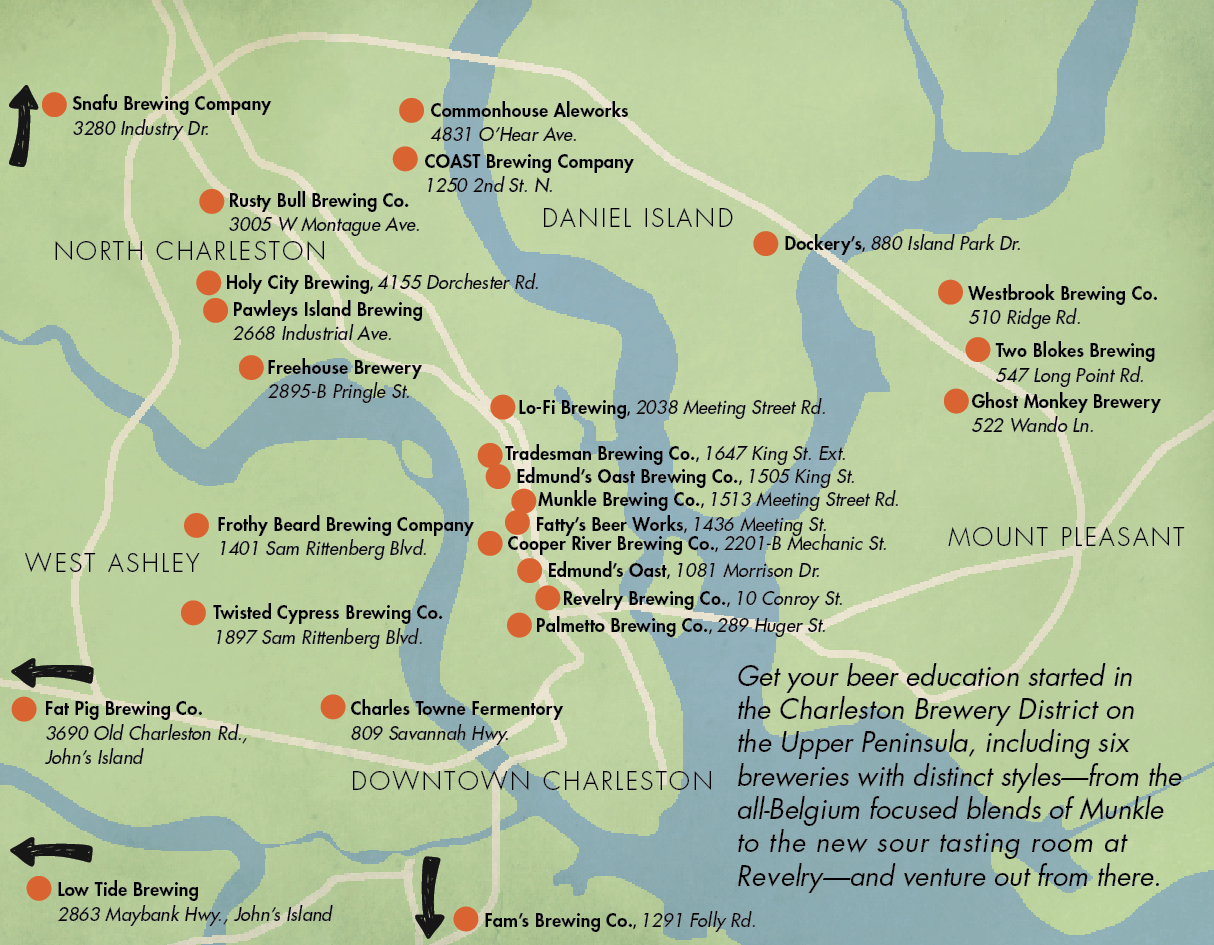

Charleston has been on a brewery boom ever since COAST co-owner Jamie Tenny’s Pop the Cap campaign got the state legislature to lift the limit to 14-percent alcohol by weight in 2007. More than a decade later, the region is fully established as a beer destination. At last count, the Lowcountry had 28 licensed breweries and brewpubs, with 26 in Charleston County, one in Dorchester, and one in Berkeley. That’s a great thing for the region, says Brandon Plyler, the state’s first certified cicerone.

“People say, ‘The bubble’s gonna burst; there’s no way we can sustain any more than we have now,’” he says, pointing out that before Prohibition, there were around 6,000 breweries in the US. “Think of how small the population was then to what it is now.” Which is to say, Plyler believes this is only the beginning. “As long as people are making great beer and marketing themselves well and making people happy, they’ll be fine.”

Credit: Map by Dee Dee Difazio

Fun fact: the word “chartreuse” comes from La Grande Chartreuse, the name of the Carthusian monastery near Grenoble, where both Green and Yellow Chartreuse liqueurs are made. That’s right, the color was dubbed after the vivid liqueurs created in 1764 and 1838, respectively. Even more fascinating, only two monks know “the identity of the 130 plants, how to blend them, and how to distill them” to make the spirits, the yellow being the milder and sweeter of the two. Head to the bar at Minero to sample it on the rocks. Or try El Satanico, Minero’s fun play on a margarita, with blanco tequila, pineapple vinegar, and fermented pineapple rinds.

Minero’s El Satanico

(Serves 1)

- 1.5 oz. Casa Pacific Blanco

- 0.5 oz. JAM pineapple vinegar

- 0.25 oz. Yellow Chartreuse

- 0.25. oz. agave nectar

- 1.5 oz. Argus Cidery Tepache

Combine the tequila, pineapple vinegar, Yellow Chartreuse, and nectar over ice in a shaker. Shake and strain into a Collins glass filled with ice. Top with Argus Cidery Tepache and serve.

Credit: Photograph by Sarah Alsati

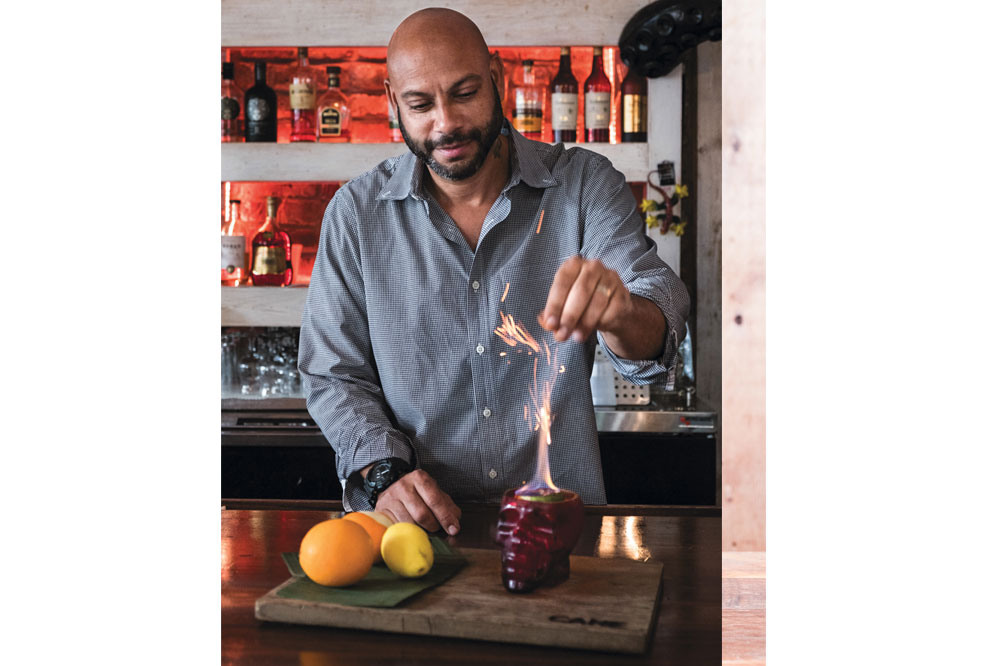

At Cane Rhum Bar on East Bay Street, owner Paul Yellin allows only one Zombie per customer. “You have one, and you feel fantastic. You have two, and you don’t know where your pants are,” says Yellin of his take on the classic tiki cocktail, made with 126-proof Jamaican rum, a 109-proof rum floater, a 151-proof flaming shot, not to mention 156-proof absinthe. A blend of fruit juices balances the high-octane drink. Sip at your own risk and remember, cautions Yellin, “There’s a reason it’s called a ‘Zombie’ and not a ‘Panda Bear.’”

Caption: Cane Rhum Bar chef-owner Paul Yellin’s three rum and absinthe zombie will light you up!

Credit: Photographs by Sarah Alsati